Jean Carroll

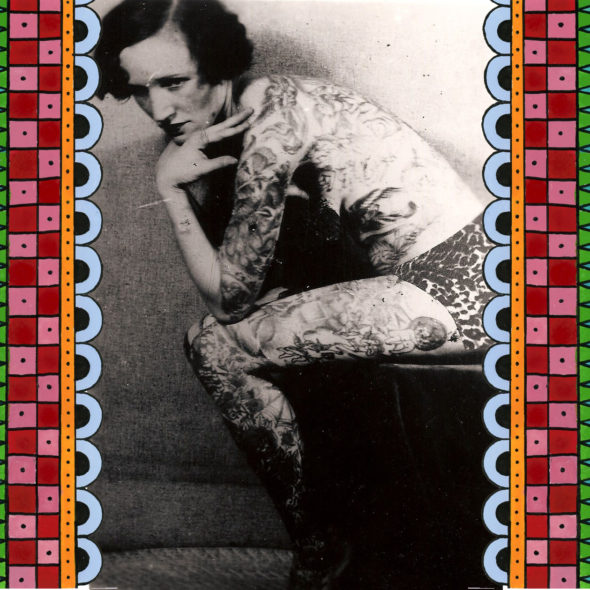

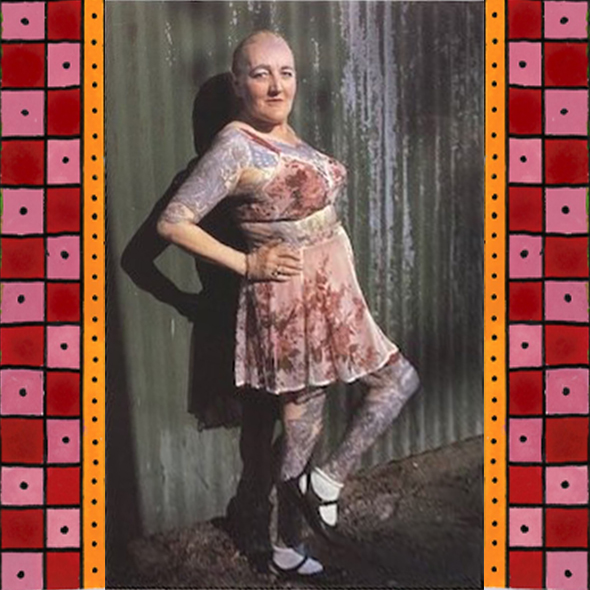

Jean Carroll, like many tattooed ladies before her, adopted a fabricated name and a fictional narrative to captivate the public’s interest in her tattoos. Crafted stories were essential for selling acts to the audience, and she ingeniously wove one around her ink. Instead of simply admitting her fondness for tattoos, Carroll’s tale revolved around her starting circus days as a bearded lady. She recounted how her desire for love led her to shed her facial hair, driven by affection for John Carson, a fellow performer on the same show.

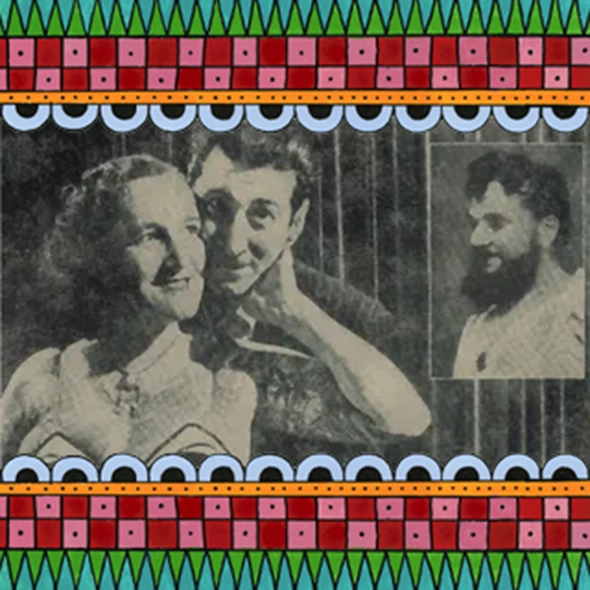

However, Carson’s feelings for her were clouded by societal norms, and he struggled to accept her facial hair. To address this dilemma, a close friend named Alex Linton, a renowned sword swallower, proposed an unconventional solution: getting tattooed to maintain her place in showbusiness. Carroll seized this idea and marketed what we think was her fabricated journey in a pamphlet titled “The Story of How I Became a Tattooed Lady,” priced at 50 cents.

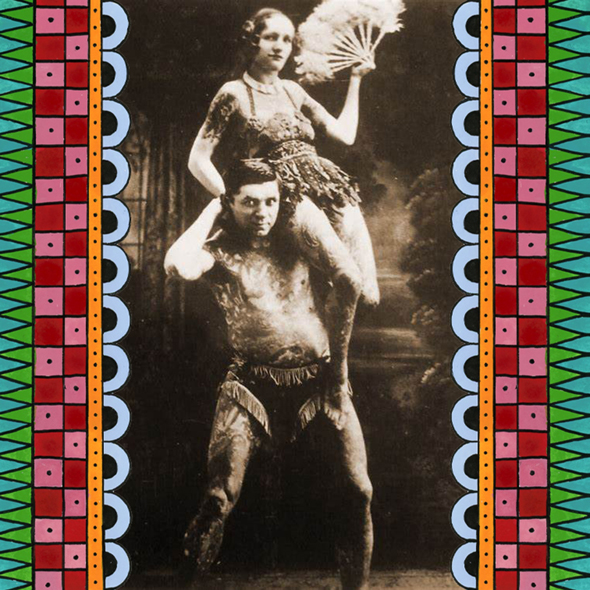

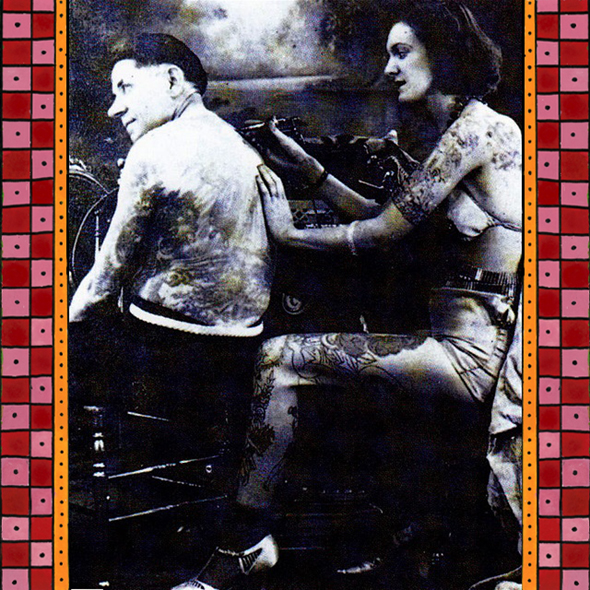

Born on September 6, 1908, as Elisabeth Furella (or possibly Fiorella) in Schenectady, New York, Carroll became a canvas for the skilled hands of Prof. Charlie Wagner, well known tattoo artist. Numerous photos captured their interactions, with one even depicting her tattooing him, raising the question of whether he might have taught her the art of tattooing.

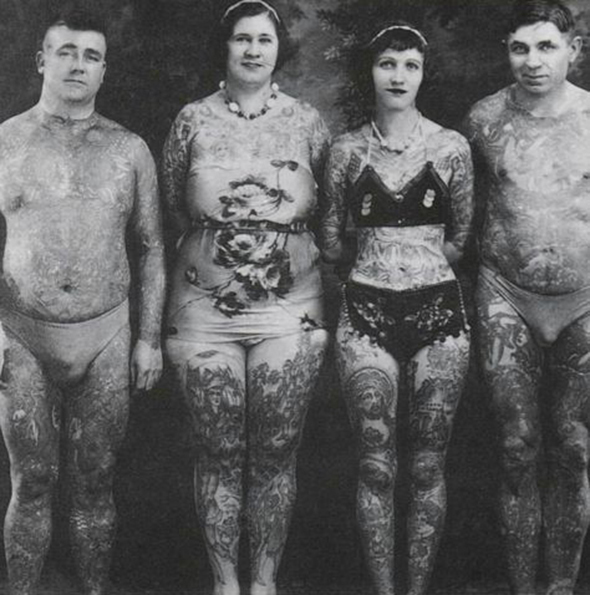

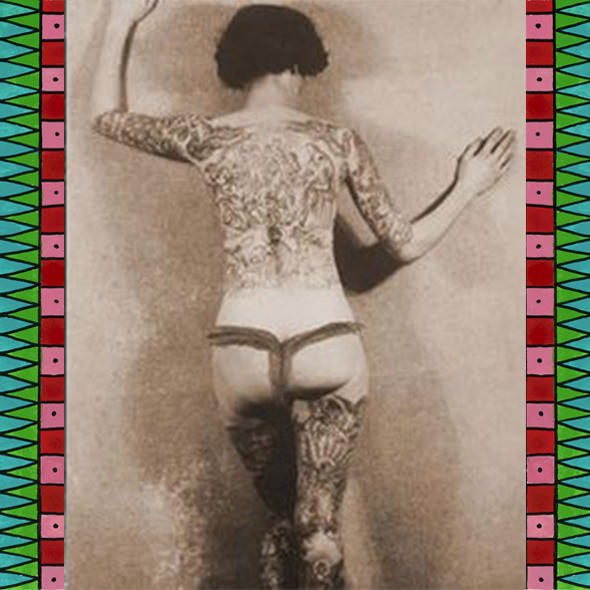

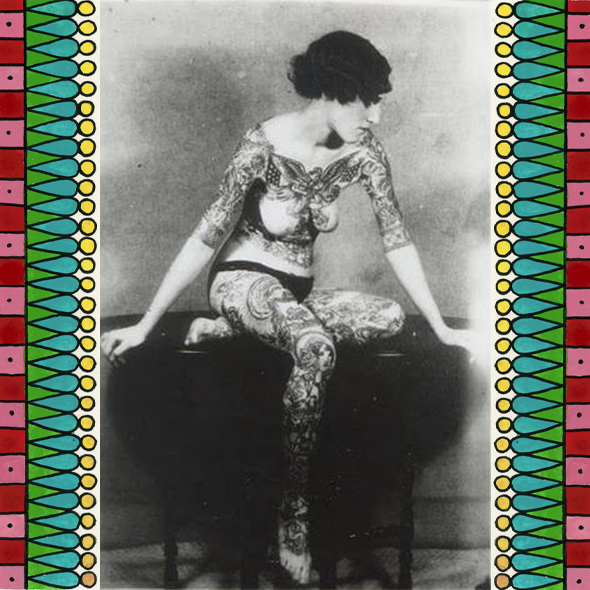

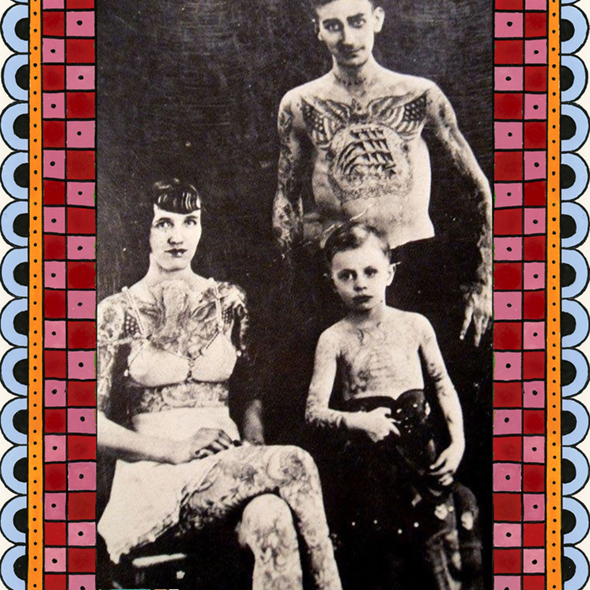

In 1936, she had a run-in with the law for theft, which was documented in a police record that also referenced her tattoos. Among her notable connections was Bernard Kobel, a photographer from the mid-19th century who specialized in the unusual and the enigmatic, particularly women. His lens captured several images of Carroll, including some nude photographs and a picture of a tattooed family. Many suspect the tattoos on the little boy in the photo were fake. The man in the image might have been Carroll’s initial husband.

Carroll’s body became a canvas for various tattoos, each telling its own story. Her chest bore an image of an angel guarding the famous aviator Lindbergh in a plane, while her stomach showcased La Piéta adorned with a rose “belt.” Angels, a Madonna and Child, and a Christ’s head with the Rock of Ages adorned her thighs.

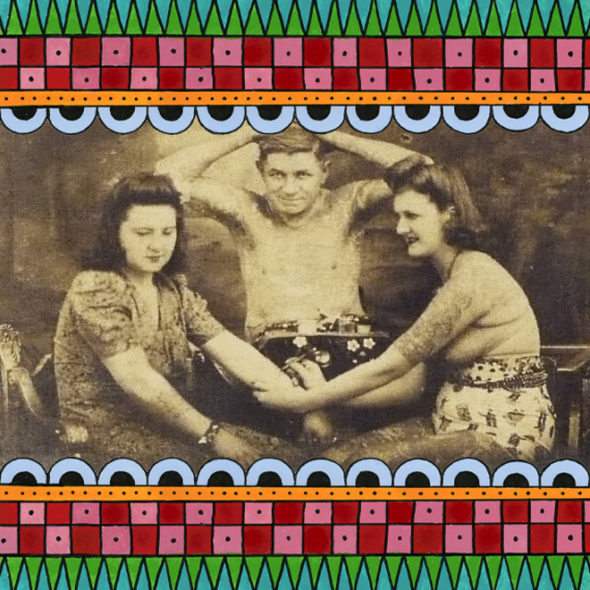

Throughout her life, Carroll continued to showcase her tattoos as a tattooed lady in traveling circuses and dime museums. This chapter concluded on July 29, 1972, with her passing in New York City. Carroll’s marital journey included two unions. Her second spouse, Larry Rapp, shared the same profession as her first husband as a “barker,” or “talker” enticing audiences to attend performances. Both husbands precede her in death and rest in the same cemetery plot, though Carroll’s final resting place remains unknown.

Two films immortalized Jean Carroll in her later years: “The Story of How I Became a Tattooed Lady,” directed by Tom Palazzolo, offered an artistic perspective on her life (available on Fandor). Additionally, Susan Milano’s “Tattooed Lady 1972,” housed in MOMA’s collection, captured Carroll’s essence shortly before her demise.